Next year will bring changes to allergy labelling. But ministers are also mulling over new rules for sugar content, calorie counts on alcoholic drinks and menus plus improved information on animal welfare. Nick Hughes reports.

The dual tasks of dealing with covid and preparing for Brexit (more on this in next Monday’s Footprint Premium) are understandably taking up a lot of industry bandwidth at the moment.

The domestic policy agenda, however, continues to move forward apace; nowhere more so than in labelling.

Here are three food labelling issues that businesses should be minded to keep a close eye on in 2021.

Allergens

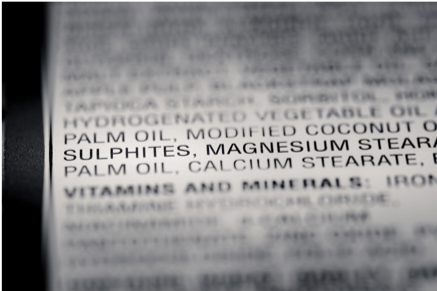

‘Natasha’s Law’, which comes into force in October 2021, is arguably the biggest piece of labelling legislation to impact the foodservice sector in decades. The law will require food pre-packed for direct sale to carry full ingredient and allergen labelling.

Businesses should also expect precautionary allergen labelling (PAL) – whereby food outlets display a warning that no guarantee can be given that any food product is entirely free of allergens – to come under greater scrutiny.

Speaking at a recent Westminster forum on the future of food labelling in the UK, Allergy UK CEO Carla Jones said approaches to PAL were currently failing people with some businesses seeing them as a disclaimer rather than a tool to inform the customer of the risk of contamination.

The Food Standards Agency (FSA) intends to review the use of PALs as part of its new food hypersensitivity strategy. Speaking at the same conference, the agency’s director of policy Rebecca Sudworth said use of PALs was on the rise with FSA survey data suggesting over half of out-of-home (OOH) businesses now using them. The FSA is prioritising work to better understand how businesses are carrying out risks assessments that inform the use of PALs. “We’re really clear as the FSA that if you use a precautionary statement [it] needs to be meaningful and underpinned by an actual risk assessment of the process that takes place in production […] rather than simply putting a statement on [the product] that you think as a business is going to provide some kind of disclaimer,” she told the conference.

Nutrition

Long-threatened calorie labelling laws are due to be brought forward early in the New Year. In its latest obesity strategy, published in July, the government confirmed plans to introduce legislation to require large OOH sector businesses, including restaurants, cafés and takeaways with more than 250 employees, to provide calorie labels on the food they sell.

Alcohol suppliers are not off the hook either. In the same strategy the government pledged to consult on its intention to make companies provide calorie labelling on alcohol including drinks sold in the OOH sector, for example bought on draught or by the glass. The consultation is due to be announced shortly. Estimates suggest alcohol accounts for nearly 10% of the calories consumed by those that drink it. Plans for labelling have split opinion: health campaigners want it; industry generally doesn’t.

Meanwhile, another consultation is looking at whether the multiple traffic light label system that has been the government’s preferred nutritional label for packaged goods since 2013 is due for a shake-up. The Department of Health and Social Care is seeking views on possible changes to the system including an assessment of whether other systems such as France’s Nutriscore or Chile’s Warning Label would be more appropriate.

Arguably this has been on the government’s ‘to change’ list for some time. “The country has voted to leave the EU… and that means we are going, once more, to have the freedom to make our own decisions on a whole lot of different matters, from how we label our food, to the way in which we choose to control immigration,” said Theresa May, then prime minister, at the Conservative Party conference in 2016.

Campaigners have already indicated they will push for front-of-pack labels to be made mandatory (they are currently voluntary) and will also push for changes in how sugar content is displayed with major potential consequences for suppliers of sugar-laden foods and drinks.

The consultation will consider whether the current 90g reference intake for total sugar on which traffic light labels are currently based should be brought into line with UK dietary advice for adults to consume no more than 30g of free sugars each day.

Free sugars are any sugars added to food or drinks, or found naturally in honey, syrups and unsweetened fruit juices. There are small differences in the definition of free and total sugars – sugars intrinsic in milk and in unprocessed fruits are not counted as free sugars – but in practice the vast majority of sugar present in most processed food and drink products is covered by both definitions.

A 30g reference intake would be a bitter blow for some products. For example, a 330ml can of Coca Cola Original containing 35g of sugar would face being labelled as containing more than your entire daily sugar allowance. Chocolate bars such as Dairy Milk and KitKat would have to be relabelled to show that a single serving contains three times more of your daily recommended sugar intake than is currently displayed on packs.

Environment

Referencing the government’s traffic light consultation, Sue Davies, strategic policy advisor at consumer organisation Which?, told the Westminster forum that environmental impact should also be considered in future changes to front-of-pack labels.

Readers with a long memory may remember a pledge by then environment secretary Michael Gove back in January 2018 to develop a new “gold-standard” label for food and farming quality. Three years later we’re still waiting for the details although there are signs that Gove’s commitment still stands. As part of the debate over the new Agriculture Bill, farming minister Victoria Prentis committed to a “serious and rapid examination of the role of labelling in promoting high standards and high welfare across the UK”.

Speaking at the Westminster forum, Rob Wells, head of food labelling at Defra, confirmed that a consultation is currently being prepared for spring 2021 which will focus on welfare labelling. Ministers and officials are considering the question of whether the consultation should also cover the foodservice sector.

Extending country of origin labelling requirements to foodservice operators is one policy that may come up for consideration given Prentice’s assertion that “consumer information” is one tool the government can use to defend the UK’s “high environmental protection, animal welfare or food standards” – information that is largely lacking for food consumed outside of the home as things stand.