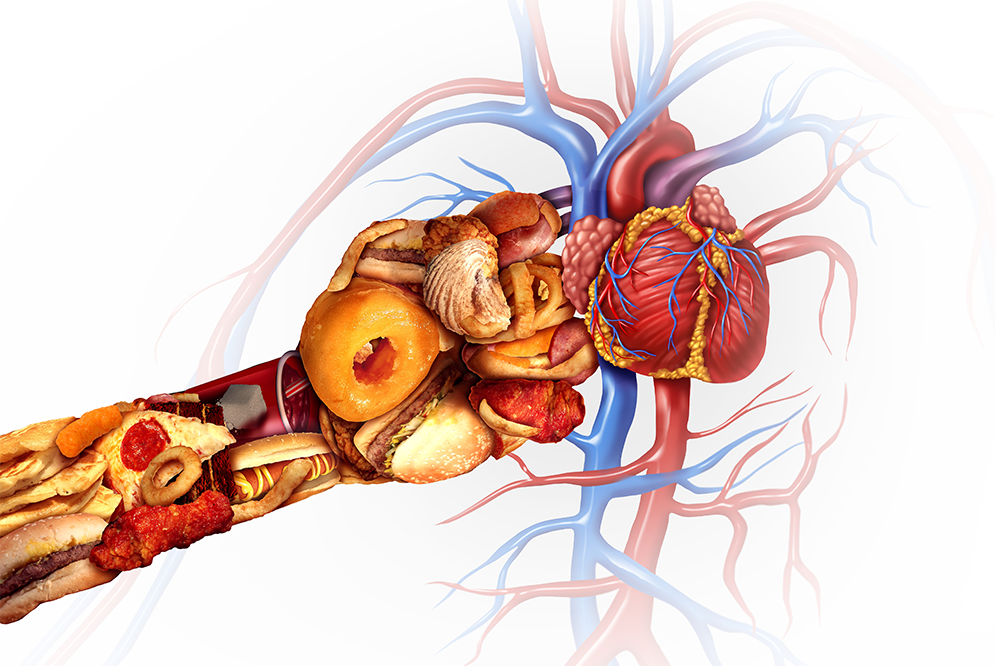

As evidence mounts over the harm caused by diets high in ultra-processed foods, policymakers will need to confront some difficult questions, says Nick Hughes.

“There’s a point where it reaches a tipping point where the thing just becomes so enormous and so impactful that you’ve got to act.”

The quote, from former Labour health secretary Alan Milburn, features in the recently published Nourishing Britain report in which co-authors Henry Dimbleby and Dr Dolly van Tulleken mine the lived experiences of leading political figures for insights into how they navigated the politics of food and diet-related ill health.

Some experts believe we have reached that tipping point with ultra-processed food (UPF). In November, the BBC aired a documentary, Irresistible – Why We Can’t Stop Eating, in which Dr Chris Van Tulleken (brother-in-law to Dolly)prosecuted the case for treating UPF as a threat to public health akin to that posed by tobacco.

Since publishing his book, Ultra Processed People, in 2023, infectious diseases doctor Van Tulleken has toured TV studios and conference rooms explaining how the science increasingly suggests humans are hard-wired to want to eat UPF to the point where it may meet the threshold for addiction.

In the new documentary, Van Tulleken explains how neuroscientists working for Unilever pioneered the use of brain scanners to determine what foods people like and deployed this knowledge to develop products that optimise palatability through texture and taste to reach the so-called ‘bliss point’.

His thesis is that UPFs are typically easy to digest and energy dense meaning people eat them incredibly quickly, thus bypassing the brain’s sensors that tell us when we’re full. When you combine their chemistry with their low cost, high availability and billions of investment in branding and advertising, UPFs literally become irresistible. Pringles even placed this irresistibility at the core of its marketing strategy with the slogan: ‘Once you pop you can’t stop’.

As evidence of the harms caused by diets high in UPF become ever stronger, the question policymakers must grapple with is how to regulate a group of foods that, based on the commonly used Nova classification system, account for more than 50% of the calories we consume in the UK.

Nuanced debate

This is easier said than done. Once the harms associated with tobacco became incontrovertible (following years of industry denial and distraction) the case for penal regulation through taxes and bans for what was essentially a recreational product became relatively easy to make.

With UPF, there is far greater nuance involved. Definitions of UPF are broad, covering a multitude of foods ranging from cereals and baked goods to confectionery and meat alternatives. Within this broad categorisation are foods that dietary guidelines would consider part of a healthy diet, like wholegrain breads and cereals. Few would disagree it’s a good thing for society if people who habitually consume white bread substitute it for wholegrain bread, or those who eat high quantities of processed meat swap some for meat alternatives.

Another challenge surrounds the evidence base. High consumption of UPF is consistently associated with an increased risk of a number of negative health outcomes, however the vast majority of studies to-date have been observational (and so can’t account for other lifestyle factors that might be driving the results), and the mechanisms driving these association are not yet fully understood. A number of randomised-control trials are underway that hope, or even expect, to show that ultra-processing is itself a risk factor and that energy density and hyperpalatability are mechanisms that drive increased energy intake from UPF, rather than a food’s specific nutritional profile.

HFSS focus

This brings us to perhaps the greatest challenge for governments considering the case for regulating UPF, including the new Labour government (health secretary Wes Streeting has previously expressed concern over the manipulative marketing strategies used by food companies to sell UPF). For years UK obesity policy, albeit largely light touch, has targeted foods based on their nutritional profile; specifically three key nutrients of concern – fat, sugar and salt. Foods that are sufficiently high in a combination of these nutrients (HFSS) have been targeted for advertising or promotion bans, while each nutrient has been singled out for voluntary reformulation targets (to little effect).

Those interviewed for the Nourishing Britain report noted how changes in nutritional science are not politically helpful to politicians who do not want to risk losing credibility by introducing a policy based on science that is later disproved or superseded. By pivoting to target UPF as a distinct group, policymakers would effectively be conceding that a decades-long approach focused on specific nutrients has been fundamentally flawed. It would also be a nightmare from a public messaging perspective having spent years hammering home the dangers of consuming too much fat, sugar and salt.

Fat, sugar and salt have been legitimate targets based on what we knew at the time, and they still might be – there is a high crossover between foods that are high in fat, sugar and salt and those that are ultra-processed, but there is also a large cohort of non-HFSS foods that are UPF.

These uncertainties and complexities help explain why there is currently no sign that UK regulators are minded to act against UPF as a distinct group. Following an evidence review in 2023, the government’s Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) said more research was needed before it could draw any firm conclusions about whether UPF causes poor health, despite finding associations between increased consumption of UPF and an increased risk of health issues such as obesity, chronic diseases like type-2 diabetes, and depression.

And in an otherwise coruscating verdict on how the current food system is making us ill in a recently published report, the House of Lords Food, Diet and Obesity Committee hedged its bets in calling for further independent research to be carried out to understand the links between UPF and adverse health outcomes.

Unintended consequences

Parts of the food industry have been quick to preach caution over regulating UPF. During a recent webinar hosted by Food Manufacture magazine titled ‘The unintended consequences of the UPF trend’, panellists aired a number of common defences (albeit some, it should be noted, did express concern over the growing evidence of UPF-related harm), including that correlation between diets high in UPF and diet-related ill health is to be expected since UPF tends to be high in problem nutrients like fat, sugar and salt. They also highlighted the important role of processing in maintaining food safety, increasing shelf life and minimising food waste. Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater, was the underlying message.

Scratch beneath the surface, however, and there are signs that businesses heavily reliant on sales from UPF are getting edgy about the threat of regulation. Stéfan Descheemaeker, CEO of frozen foods giant Nomad Foods, won praise from campaigners recently when he came out in support of mandatory reporting of healthy product sales, and a tax on HFSS foods that promotes reformulation and innovation. Descheemaeker noted proudly how 93.3% of the company’s portfolio by sales volumes is considered non-HFSS. “As the chief executive of one of the world’s largest frozen food businesses, we recognise the responsibility we have in offering nutritious, accessible and tasty food,” he said.

Descheemaeker was notably quieter on the subject of UPF which, for a company whose brands include Birds Eye fish fingers, Goodfella’s pizza and Aunt Bessie’s Yorkshire puddings, is perhaps unsurprising. Is it possible that in offering full-throated support for further action on HFSS foods, Descheemaeker was hoping to push the government further down a path from which it is difficult to retreat?

Binary choice?

Tackling HFSS foods remains the core plank of government obesity policy. As recently as this month, Labour confirmed the final details of advertising restrictions for junk food (HFSS) products which will mean ads on television will only be allowed past the 9pm watershed from October 2025.

It is too simplistic to argue that governments face a binary choice between regulating foods based on HFSS or UPF – there may be a third way whereby regulators try to integrate key UPF markers like the presence of additives into nutrient profiling models.

Yet at some point tough choices will need to be made. Health campaigners have consistently called for mandatory reformulation targets for fat, sugar and salt given the failure of voluntary programmes to deliver meaningful improvement. But if you’re going to force manufacturers to invest millions of pounds in the research and technology needed to reduce problem nutrients, you can’t then slap warning labels or taxes on reformulated products on the basis that their processing makes them intrinsically unhealthy.

Sickly symptom

There is a broader point here too: that any efforts to regulate UPF will fail if they fail to change the context in which we buy and consume food. UPF is the symptom of a society that values economic growth and investor returns over collective wellbeing; that prefers to subcontract the job of feeding the population to those incentivised by profit rather than those who pick up the tab for the cost of treating diet-related ill health and repairing environmental harm.

The instinct of ‘big food’ is to turn any new restriction into an opportunity. It’s not hard to imagine a future where advertising bans on UPF spur brands into finding new, more ‘natural’ ingredients that mimic the properties and functions of industrial additives and allow businesses to market products with ‘cleaner labels’. Such replacement ingredients will still be bound by the need to support the low cost, long shelf life, mass production model demanded by multinational manufacturer and retailer supply chains.

By tackling UPF through a narrow lens of taxes and restrictions, we risk simply substituting one bad food system for a slightly less bad version. Moreover, if you’re going to start regulating UPF you have to give people the means to replace these foods in their diets. It would be politically and morally misguided to levy a tax on UPF as a ‘silver bullet’ solution and force those who rely on convenience products to spend more of their income on feeding themselves.

The only solution to the harm caused by UPF is the same as it is to the environmental harm caused by intensive agricultural production or the unrelenting pressure on farmer livelihoods – structural food system reform that makes whole or minimally processed foods the affordable, accessible choice for all.

Speaking during a recent webinar organised by the University of Cambridge, Van Tulleken flipped the question over how best to regulate UPF on its head. “We want justice and equality in our food system,” he said. “That I think will inevitably lead to less UPF, but [less UPF] shouldn’t be the goal.”

In announcing plans for a new food strategy last week, Labour hinted that it gets the need for horizontal reform of the food system that straddles multiple government departments – the type of reform politicians interviewed for the Nourishing Britain report said was the hardest to deliver as they rub up against competing interests and priorities.

“The vast majority of the food-related health policies of the past three decades have been abandoned, derailed, watered down, delayed into extinction, lost in the system or forgotten altogether,” write Dimbleby and Dolly Van Tulleken in their commentary on the report.

If the threat from UPF is as existential as Chris Van Tulleken and others believe it to be, politicians cannot afford to get this wrong again.