The food labelling agenda continues to progress at pace with calories, allergens and eco-labels under the spotlight. Nick Hughes reports.

From mandatory requirements for calorie labelling to voluntary eco-labelling schemes it’s a tall order for businesses to keep a handle on the latest developments in food labelling. Helpfully, a recent Westminster food and nutrition forum on the future for food and drink labelling in the UK shed some light on a range of labelling issues relevant to food and drink businesses. Here are some key takeaways for those looking to stay ahead of the labelling curve.

Eco-labelling alignment remains elusive

In May, Footprint provided a summary of what we described as an “eco-labelling landslide” which has seen a rapid proliferation of schemes in development alongside projects to establish common environmental metrics. Six months later two of the most significant players in this space – IGD and Foundation Earth – updated the forum on where they are now.

IGD head of sustainability Harriet Illman explained how the organisation has been working on both the “back end” and “front end” of its scheme which aims to create a harmonised environmental label for food businesses. At the front end, IGD has been leading a pilot of prototype environmental labels with four food retailers – Co-op, Morrisons, Sainsbury’s and Tesco – to test consumer understanding of eco-labelling. Results from the virtual trials, which are assessing the effect of scoring systems across both alphabetical (e.g. A to E) and numerical five-point scales, are expected in December and will inform the next stage of development of a harmonised scheme.

Illman said back end work has involved developing the methodology behind how the environmental impact of products is calculated and then scored. This is a contentious subject: much of the debate over the validity of eco-labelling schemes has focused on their reliance on secondary data that uses global or regional averages for indicators like greenhouse gas emissions, versus primary data that is supply-chain specific and therefore more accurate but much harder and more time-consuming to capture. Illman said IGD is looking primarily at using secondary data refined to reflect a UK market but with the ambition of moving to a scheme that includes primary data. It might not be “perfect from the start” but it provides a base to build from, she said.

Criticism of this approach had already been voiced earlier in the forum by Fidelity Weston, a livestock farmer and chair of CLEAR (the consortium for labelling for the environment, animal welfare, and regenerative farming), which is calling for mandatory method of production labelling on all foods at all points of sale. Weston argued that the use of synthesised global data for eco-labels did not distinguish between different methods of farming across different countries and therefore would not reflect the true environmental and social realities on the ground. “This is dangerous for farming, public health, ecosystem health and much more,” she said.

Jago Pearson, chief strategy officer at food supplier Finnebrogue and chairman of Foundation Earth, agreed that an eco-label needed to be based on life cycle assessments (LCAs) and use as much primary data as possible. He noted how this was currently a “huge technical and logistical endeavour” but that in doing so eco-labels would also provide an incentive for farmers to improve the environmental footprint of their products. An eco-label “needs fundamentally to allow two products of the same type to be compared based on credible data”, said Pearson.

Since launching in June last year Foundation Earth has secured the support of companies including Costa, Marks & Spencer and Greencore who have trialled its eco-labels during a pilot phase. Pearson said the optimal environmental label of the future needed to be run and governed by an independent organisation and also needed to be harmonised across Europe and even internationally in the longer-term. “We can’t have a situation where Unilever is using one scheme, Nestlé [is] using another and Pepsi [is] using another,” he said and called on the eco-labelling “community” to “find a way in which we can work together”. For now at least, the pursuit of harmony over eco-labelling continues.

Calorie labelling consistency is key

Calorie labelling legislation came into effect in England in April 2022 making it a legal requirement for large businesses with more than 250 employees, including cafés, restaurants, and takeaways, to display calorie information on non-prepacked food and soft drinks.

UKHospitality policy director Jim Cathcart told the forum that businesses in England had rolled out calorie labelling successfully despite a challenging trading environment, albeit certain operators are still getting to grips with the vagaries of the new legislation. Cathcart explained how UKHospitality has been supporting businesses who are unsure how to interpret government guidance, for example where they provide flexible food offers like buffets and carveries, or build your own burgers.

UKHospitality’s monitoring of consumer sentiment had so far picked up mixed views from customers according to Cathcart with some liking calorie labelling and using it to inform their choice of meal and others disliking it and/or ignoring it.

Both Scotland and Wales have this year consulted on plans to make calorie labelling mandatory in the out-of-home sector. Cathcart urged policy makers to prioritise consistency in approach between the devolved nations both to support customer familiarity with calorie labelling and to spare businesses that operate across borders the burden of having to meet different requirements in different markets. He noted how some companies in England that operate across borders are already putting calories on menus in Scotland or Wales to prevent them having to produce and print a separate set of menus for each nation.

Allergen law must keep up with plant-based trend

The hospitality sector in England implemented calorie labelling just months after full ingredient labelling for pre-packed foods for direct sale became a mandatory requirement. Footprint then reported in June how experts are split over a requirement for out-of-home businesses to provide written allergen information for non-prepacked foods.

It all points to the fast moving nature of the allergen agenda amid a growing prevalence of allergy-related ill health – there has been a 500% increase in food-related hospital admissions since 1992 according to Cherry Hagger, food allergy awareness office for Allergy UK.

One issue on which campaigners are trying to engage businesses is that of emerging allergens from novel foods, in particular meat alternatives. Hagger told the forum that although plant-based diets have positive benefits for sustainability many plant-based products contain hidden allergens that are not among the 14 required by EU law to be highlighted on product labels. Legumes like chickpeas and peas are increasingly being used to make meat alternatives which may explain why reports of legume allergy are on the rise, according to Allergy UK.

In the absence of legal requirements Hagger highlighted the importance of businesses providing voluntary information on legume-based allergens. Hovis for example has added an FAQ to its website explaining that the sources of the vegetable proteins found in its hot dog rolls, burgers and seeded batch bread are from peas, potatoes and fava beans.

Insect-based foods and supplements – while not as well-established in the market – also need to be treated with caution said experts. Both Hagger and Katrina Andersen, senior associate at law firm Osborne Clarke, noted how research is showing a tendency for people who have a crustacean allergy (one of the 14) to also be allergic to insects. In response, Andersen highlighted how some producers of insect-derived foods are voluntarily adopting crustacean allergen warnings on their products.

Does labelling really shift the dial?

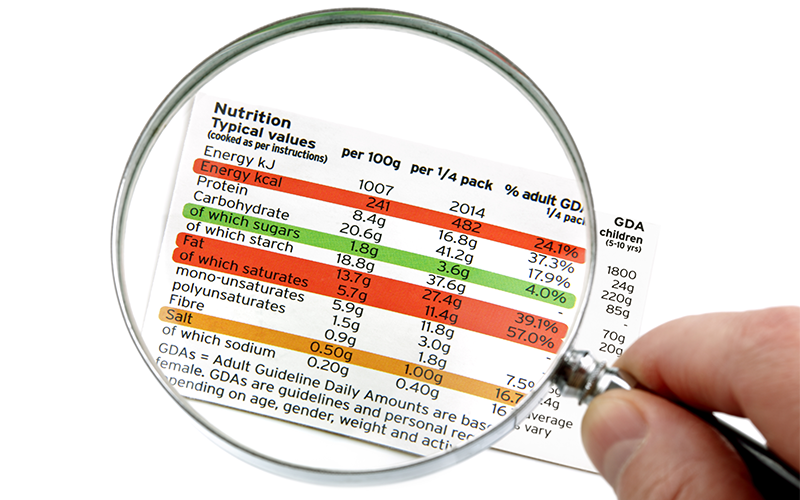

For all the focus on labelling by businesses and policy makers there remains a legitimate question about how much it really changes behaviour? For nutritional and environmental labelling in particular the evidence presented by Jack Tadman from research company Opinium suggested labelling may be a relatively blunt tool in shaping consumer habits. Take traffic light labelling, which has featured on UK grocery packaging in some form for well over a decade yet 11% of people are still unaware of it and 23% are aware of it but don’t know what it means. Almost half (45%) of the UK population say they rarely or never look at traffic light labels.

Similarly with recycling and packaging symbols the evidence suggests they are not enabling informed decisions but rather adding to people’s confusion. The vast majority of people (ranging from 61% to 77%) surveyed by Opinium in 2020 misattributed the meaning of eight common recycling and packaging symbols such as the Mobius loop – a triangle composed of three arrows looping back on themselves in a clockwise direction that signifies the packaging is capable of being recycled but is not necessarily accepted by all recycling collection facilities.

Will a new wave of eco-labels bring newfound clarity to the task of choosing more sustainable products? Or will they simply add an extra layer of complexity to an already bewildering labelling landscape? We won’t have to wait long to find out.