The new government has shown an early willingness to intervene in the market but lacks a cross-cutting strategy to deal with food system challenges. By Nick Hughes.

In sprinting parlance, the first hundred days of a new government are an opportunity to explode out of the blocks, get quickly into your stride and show the opposition (and the viewing public) that you mean business.

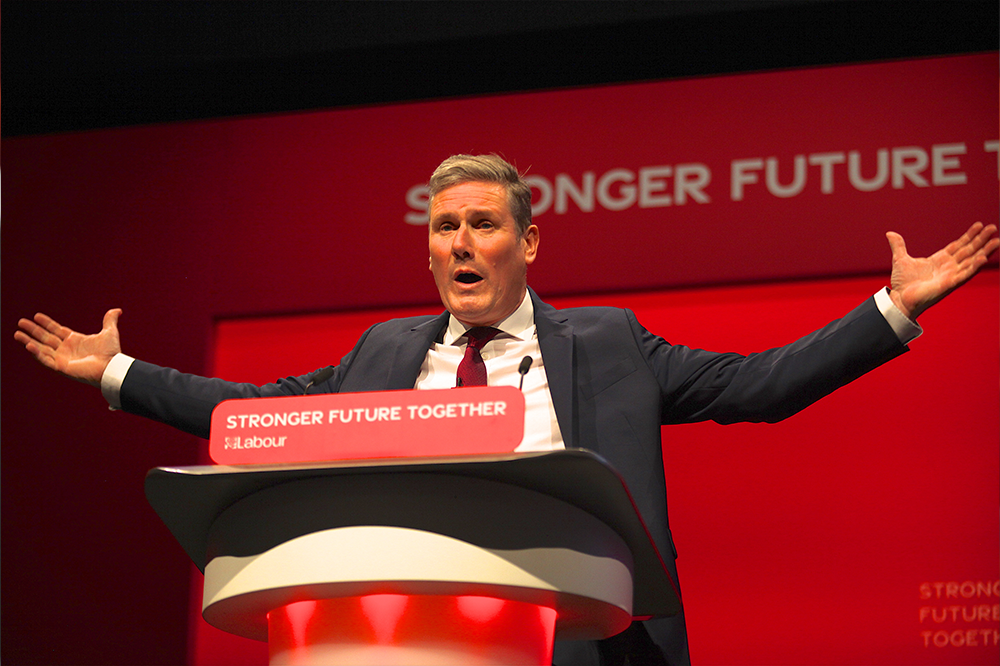

Labour, alas, has given every appearance of competing in a three-legged race as it wobbles and stumbles through the early months of its tenure amid tanking approval ratings and unflattering headlines.

It’s important to remember these are still early days; embarrassment caused by the freebies scandal and the salary of Sue Gray will likely be an irrelevance by the time voters next come to put a tick in the box in a UK general election.

But while specific pieces of bad news may in time disappear from voter memories, broad narratives and perceptions that take root in the early days of a new administration can be much harder to shift.

Food mission

Action to-date on food and farming is in many ways a microcosm of the broader critique of Keir Starmer’s leadership with some concrete policy announcements set within the context of a government that is struggling to spell out a wider vision for the food system it wants to help create.

As Sue Pritchard, chief executive of the Food, Farming & Countryside Commission, noted in a blog following the Labour Party conference in Liverpool, food is not yet a stated government mission (there are five in total) but is integral to the delivery of the others.

That’s especially the case where the mission to ‘improve the NHS through health and care service reform and reducing health inequality’ is concerned. Labour has already shown itself willing to be more interventionist on food and health than the previous Conservative government and both health secretary, Wes Streeting, and minister for public health and prevention, Andrew Gwynne, have spoken publicly of the new government’s desire to embed a culture of prevention across the health service.

Policies already announced with the aim of creating a healthier food environment include a ban on the sale of high caffeine energy drinks to under 16s and confirmation that a pre-watershed ban on TV and online advertising of foods high in fat, sugar and salt (HFSS) will come into force in October 2025.

Another manifesto commitment, the rollout of free breakfast clubs to all primary school children, will begin in April with a pilot involving 750 schools.

Political pressure

Yet Labour is under to pressure to go much further and faster. Campaigners, alongside national food strategy author Henry Dimbleby, continue to call for mandatory reporting of key health metrics by large food businesses, while there have been calls too for the soft drinks industry levy to be expanded to other sugary drinks and products as well as highly salted foods.

Regardless of its merits, the latter could be politically challenging for a government which has identified achieving sustained economic growth as one of its five core missions for its first term in office (albeit the Treasury is desperate to find new ways to raise tax revenues).

By contrast, a requirement for greater data transparency feels far more palatable – not least because many businesses are supportive of the principle. Tesco, Iceland and Nomad Foods, along with three institutional investors, recently called for companies to be legally required to report on the percentage of revenue generated from sales of HFSS products.

Earlier this month, a group of leading food businesses including Tesco, Nestlé, Compass Group and Bidfood, called on the government to require companies to publicly report their food waste data, arguing that it would incentivise better behaviours and more efficient processes, and encourage more action to be taken across the whole industry.

Dither and delay

Yet just like the Conservative government before it, Labour continues to prevaricate. Creating a roadmap to move Britain to a zero waste economy has been named as one of new Defra secretary of state, Steve Reed’s, five overarching priorities for his leadership of the department, but with a few exceptions (which we shall explore later), his department has yet to put much meat on the bones of these policy pillars.

There are questions too over the future of the food data transparency partnership (FDTP), established by the previous government to act on Dimbleby’s call for better reporting and accountability from businesses. The health working group hasn’t met since prior to the election in April and although the eco working group did meet last month, Defra is remaining coy as to the government’s intention – or otherwise – to take forward the work of the groups.

There are further unanswered questions over new deforestation rules. The previous Conservative government was in the process of legislating to make it mandatory for large companies to carry out due diligence checks to ensure there is no illegal deforestation in their supply chains for forest-risk commodities such as soy, beef and palm oil. But the legislation was subject to numerous false starts and never made it onto the statute book before the general election, while there was no mention of it in Labour’s King’s Speech in which the government set out its legislative agenda for the current session of Parliament.

In August, the Retail Soy Group (RSG), whose members include ten of the biggest UK grocery retailers along with the British Retail Consortium (BRC), wrote an open letter to Reed calling on him to introduce and adopt the forest risk commodities legislation within his first hundred days in office.

With the EU having recently announced a 12-month delay in the application of its own deforestation regulation due to pressure from overseas governments, progress on a critical issue is on ice despite almost 16 million acres of global forest having been razed in 2023, according to a new report from research group Climate Focus.

Transformative tech?

Where Labour has been proactive is in taking forward Conservative-initiated legislation to create a lighter-touch regulatory regime for so-called precision breeding technologies, such as gene editing, where the DNA of plants or animals is tweaked in a precise way to select for desirable traits.

Last week, Labour confirmed it would bring forward the secondary legislation needed to make this new regime a reality as soon as parliamentary time allows with farming minister, Daniel Zeichner, claiming the technology will “boost Britain’s food security, support nature’s recovery and protect farmers from climate shocks”.

Such statements are fiercely contested. Leonie Nimmo from campaign group GM Freeze suggested “the fantastic promises the government is making about the benefits of so-called precision bred crops could have been cut and pasted straight from a biotech brochure” adding that “twiddling with genes” is not a solution to “complex, systemic” problems.

It’s clear, however, that Labour is keen to explore the potential in cutting edge technologies to support food security and sustainability. As a further example, the Food Standards Agency, in collaboration with Food Standards Scotland (FSS), has just been awarded £1.6m in funding from the government’s engineering biology sandbox fund (EBSF) to launch an evidence-gathering programme on cell-cultivated products like meat. The information gathered by a team of experts will inform recommendations about product safety with the aim of helping the regulators process cell-cultivated product applications more swiftly.

Crisis in confidence

Farmers may be looking on with envy over the availability of fresh cash for food tech amid anxiety over Labour’s refusal to commit to increased funding for environmental land management schemes (livestock farmers will also be wondering how they fit in to a policy push for cultured meat). Figures released by Defra over the summer showconfidence within the farming sector remains low. More recent research by Riverford as part of a new campaign showed 61% of farmers now fear they will go bust in the next 18 months – up from 49% last year.

Confidence can only be restored (or otherwise shattered decisively) once the government charts a very clear path for the future of the food system; one that grapples with the interrelated challenges of farmer livelihoods, food security and resilience, climate change, diet-related ill health, food access and affordability, and many others besides.

If this sounds fanciful then allow me to take you back 14 years in time to the Food 2030 document, produced in the dying days of the last Labour government led by Gordon Brown, in which a comprehensive set of priorities included: enabling and encouraging people to eat a healthy, sustainable diet; ensuring a resilient, profitable and competitive food system; increasing food production sustainably; reducing the food system’s greenhouse gas emissions; reducing, reusing and reprocessing waste; and increasing the impact of skills, knowledge, research and technology.

Governing is a marathon not a sprint and Labour should be afforded some time to flesh out is own detailed plan for 2030 and beyond. By delving into the past, ministers might just find a vision fit for the future.

Leave a Reply